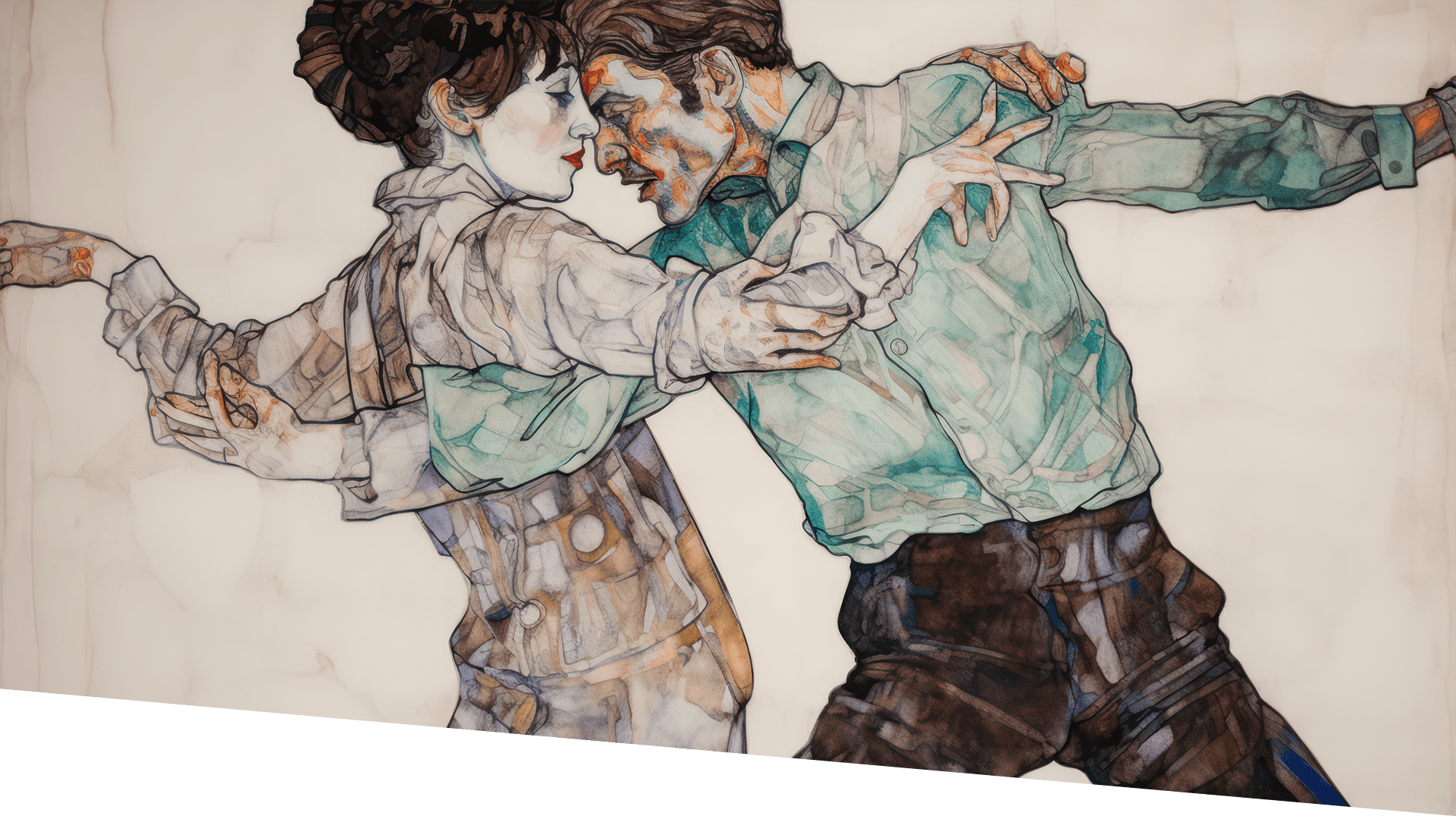

Ballet: A dance of star crossed lovers

BY DANIEL RUEDA BLANCO

“From forth the fatal loins of these two foes,

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life”.

In this extract from William Shakespeare’s celebrated Romeo and Juliet, the English writer defines the archetypical concept of “star-crossed lovers”: Based on the astrological idea that the position of the stars rule over people’s fates, this refers to the bonds of love that are doomed from the start. In other words, lovers who are not meant to be. Their path-crossing, as well as their (usually) tragic destiny, are inevitable.

Like William Shakespeare, composers have also been inspired by this idea of “impossible love”; either heard of on ancient stories and myths (like Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas, based on Virgil’s Aeneid), or based on their own personal experiences (well known is the example of Berlioz and his Symphonie Fantastique, composed after an experience of unrequited love). Being a broken heart so poignant and sorrowful, so quintessential within our human nature, that we can internalize it even without the spoken word, stories of star-crossed lovers have served as inspiration also for ballets, which depict them precisely without the spoken word, but through dance, body expression and music.

How do ballet composers depict then, musically, this soulful idea of impossible love? Let’s have then a glimpse on the ballet highlights presented during this season of the Aarhus Symphony Orchestra, to find some answers:

Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka narrates the love-triangle between three puppets on a Russian Shrovetide Fair: Petrushka, full of self-pity, is in love with the Ballerina, but she prefers the Moor. During the second scene of the ballet, we hear Petrushka’s love for the Ballerina, in a light and caressing melody of piano and piccolo; then repeated with a weeping flute counterpoint (Petrushka’s self-pity for the Ballerina’s lack of feelings towards him). Later, when the Ballerina appears, Petrushka’s overexcitement through leaping melodies and noisy orchestration scares her, who runs away leaving him in frustration. We hear the puppet’s grotesque cursing through the famous Petrushka Chord in fortissimo: a combination of the chords of C and F-sharp -a very dissonant interval or Tritone, also called diavolus in musica:

Although not a ballet in a strict form, Leonard Bernstein’s celebrated West Side Story is a musical: a synthesis between music, theatre, and dance. Through the acclaimed choreography of Jerome Robbins, and a fusion of jazz and Latin rhythms, it depicts, inspired by Shakespeare, the tragic love between two members of rival gangs in Manhattan. Here the Tritone is as well a symbol of discord, in this case between the two gangs (Jets and Sharks); and it is constantly present during the opening Prologue:

The Tritone seeks a resolution in one of the musical’s highlights: When the main character Tony sings “Maria”, proclaiming his love for the lady, the Tritone resolves in harmony; maybe portraying the hope for union between them and peace between the gangs?

We hear the Tritone once more in the last chords at the end of the play: a light, hopeful C major, with a deep eerie F-sharp on the bass: After tragedy fell upon the two lovers, are the rival gangs having peace, once and for all?

Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet, based on Shakespeare’s work, is full of musical motives that transform alongside the characters. When we encounter Juliet for the first time, she is a young girl, accompanied by three musical themes: leaping brilliant melodies (Juliet as a child), a tender melody and, when she is introduced to her arranged fiancée Paris, a grieving melody: a premonition to a love tragedy.

This grieving melody fulfils this premonition twice, depicting Romeo’s death and Juliet’s mourning for her beloved.

As well, during the Balcony scene, we hear the soaring theme of Romeo and Juliet’s love, ascending with the dancers to a moment of full love and ecstasy…

…but it returns at the end of the play, variated by dissonances and a darker orchestration, depicting Romeo’s descent into sorrow after Juliet’s apparent death.

Nevertheless, not every story of star-crossed lovers has a tragic conclusion.

Albert Roussel’s Bacchus et Ariane (most of all known for the second Orchestral Suite) shows us a story of Greek mythology with a colourful and strong orchestration. The second Act of the ballet begins with Ariane waking up in the island of Naxos, looking for her beloved Theseus, unaware that he had abandoned her. Falling in despair after realizing the truth, she attempts to finish her life. Broken rushing melodies without any centre or direction, and a heavy dissonant orchestration, depict her despair.

Just before falling from the top of the island, Greek god Bacchus (God of wine and ecstasy) catches her. His charm and joy -as opposite of Theseus- quickly make Ariane forget her beloved. When they kiss -depicted by a soaring melody of the horns-, the island is filled with enchantment and life. Soon the previous “formless” music gains a centre and a direction:

After falling in love and dance a wild Bacchanale, Ariane is carried by Bacchus into Olympia, where he crowns her as a goddess. Alongside the Bacchanale rhythms, we hear the soaring horns again, this time to a brilliant and ecstatic conclusion.

Om forfatteren

Daniel Rueda Blanco er Aarhus Symfoniorkesters assisterende dirigent for sæson 22/23. Blanco er født i Colombia og færdiggjorde sidste år sin kandidat på University of Music and Performing Arts i Wien. På universitetet fik Blanco for første gang øjnene op dirigentfaget og har i dag som 29-årig allerede høstet mange roser for sit arbejde. Han vandt bl.a. dirigentprisen ved Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional de Colombia i 2017 og blev i 2019 tildelt en speciel pris af Filarmonica George Enescu til den internationale dirigentkonkurrence Jeunesses Musicales Bucharest.